This is a story about dissent.

1

“I was scarcely eighteen years of age,

When into the army I did engage,

I left the homestead in full content

To join the forty-second regiment.

To Preston barracks I then did go

To put in some time in that depot,

But out of trouble I never was free,

For my captain took a dislike to me.”

— From the street ballad McCaffery (sometimes called McCafferty), as performed by Peter Reilly on The Folk Songs of Britain Volume 8: A Soldier’s Life for Me.

In an interview with the American ethnomusicologist Alan Lomax in 1953, the wandering Scottish singer, and the last ‘King of the Cornkisters’, Jimmy MacBeath recalled the police chasing him in Peterhead for singing the street ballad McCafferty in public. MacBeath told Lomax that he was fortunate to escape with a fine of ten shillings because had he been in the army where he’d originally learned the song his punishment would have been far worse: “I’d get shot.” Despite MacBeath’s apocryphal story of execution, he was right when he told Lomax that the song was “against the government and the British Army.”

Written by an anonymous composer, and sung to the air of The Croppy Boy, the ballad concerned the fate of Patrick McCaffery, who joined the 32nd Regiment of the British Army in October 1860, aged 18. Patrick McCaffery stood at five foot four and had a fair complexion. He had disputed origins: Some contemporary reports have him as a native of Aughnacloy, Co. Tyrone, before his family moved to Belfast and then on to England, while others have him originate in Athy, Co. Kildare. No matter where he came from, through his struggle against a superior officer he achieved a kind of infamy that still resonated with three dissenting actors a century after his death.

2

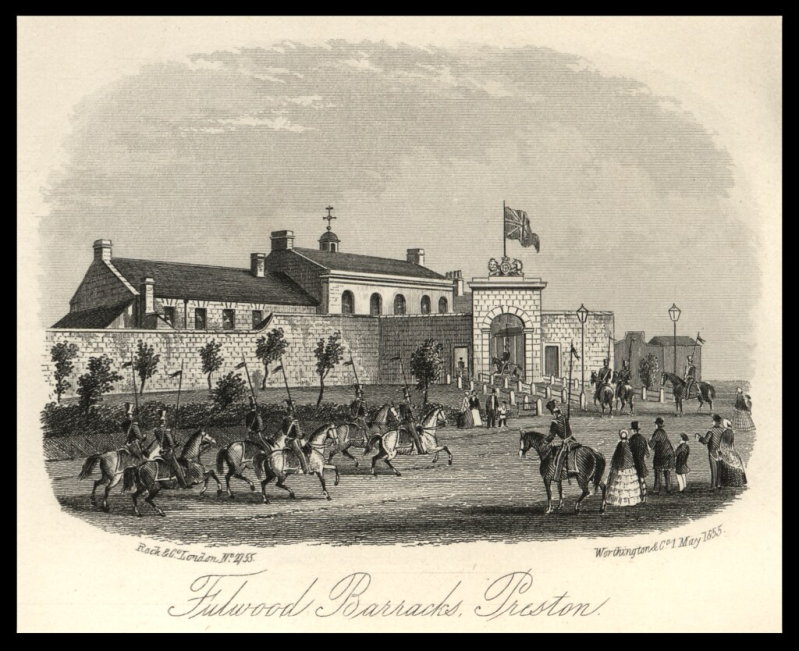

“A loaded rifle I did prepare

To shoot my captain on the barrack square . . .”

On Saturday, 14 September 1861, Private Patrick McCaffery took his Enfield no. 106 rifle down from the wall of his room at Fulwood Barracks, near Preston, walked out into the barracks square, took a knee, and fired at Captain John Hanham at a distance of 60-65 yards. McCaffery’s shot initially missed its intended target, striking Colonel Hugh Dennis Crofton on his right side. The ball sliced through Crofton’s left lung before hitting Hanham’s left arm and lodging in the lower part of his thigh. Crofton died the following night at 10:15, while Hanham died 13 hours later. Both men left a spouse and young children behind.

Colonel Hugh Dennis Crofton

“As I was standing on guard one day

Some soldiers’ children came out to play,

From the officers’ quarters my captain came

And he ordered me to take their parents’ names.

I took one name just out of three,

For neglect of duty he then charged me,

To the orderly room the next morning I did appear,

But my sad story he refused to hear.”

The morning of the murders, Private McCaffery had appeared before Colonel Crofton, charged with neglect of duty after Captain Hanham had ordered him to take the names of some disorderly barracks’ children while on picket sentry near the officers’ quarters the day before. McCaffery’s mortal sin was to return to his captain with only one name.

Hanham ordered him to the guardroom where he remained overnight until his appearance before Colonel Crofton. McCaffrey told his colonel: “I did my best, the children ran away, and I could only get the name of one of the parents.” Crofton confined him to barracks for 14 days, and further punished him to suffer pack drill with his knapsack on his shoulders.

According to another soldier from the barracks, McCaffrey had previously appeared before Crofton and the resultant punishments must have lingered in his mind as he prepared for another spell in confinement. This soldier wrote in a private letter:

“McCaffery had been up before the colonel two or three times lately for very trivial things, and has been occasionally confined to barracks. A short time ago they gave him seven days in cells, and all his hair was cut off his head.”

This final punishment proved too much for the young soldier, who said: No more, and resolved to take his revenge against Captain Hanham.

“It was my captain I meant to kill,

But I shot my colonel against my will.”

Following the murders, McCaffery had his shoes and braces removed, and his hands restrained. Captain Elgee, chief of the county constabulary, together with Superintendent Robert Green, arrested him and removed him to the Preston House of Correction. During interrogation, he said in defence of his actions: “I did not intend to murder them.” Later, in admitting to his preferred target, he said: “I did not intend to shoot the colonel, I meant it for the captain, however it does not matter much.”

The inquest into the murders took place on the Monday and Tuesday of the following week. After retiring for two or three minutes, the jury returned with a verdict of “wilful murder” against Patrick McCaffery. Those in the court could hear the notes of Dead March in Saul as the body of Colonel Crofton had arrived at the train station across the road before conveyance to his family. The coroner signed the warrant committing McCaffery to the Lancashire assizes on Thursday, 12 December 1861, before a Mr Baron Channel.

“At Liverpool assizes my trial I stood,

Says the judge to me, ‘McCaffery,

Prepare yourself for the gallows tree’.”

At the assizes Patrick McCaffery stood at the bar in the uniform of the 32nd Regiment. A Mr Russell, who defended McCaffery, argued that Hanham had mistreated his client:

“Unjust treatment he had received at the hands of Captain Hanham, and that for a simple offence the prisoner had been placed under arrest, had passed a sleepless night and been subjected to the degradation of confinement to barracks. Smarting under the indignity of the disgrace of imprisonment in the guard room by the orders of Captain Hanham was it unnatural of him to take revenge for the harsh treatment of his officer?”

The jury needed only ten minutes to reach a verdict: Guilty of wilful murder. The judge donned the black cap and sentenced him to death:

“I pronounce upon sentence according to the law, that you be taken from hence to the place from which you came, thence to the place of execution, and that you be there hanged by the neck until you be dead, and that your body be buried within the precincts of the prison in which you were last confined, and may God have mercy on your soul.”

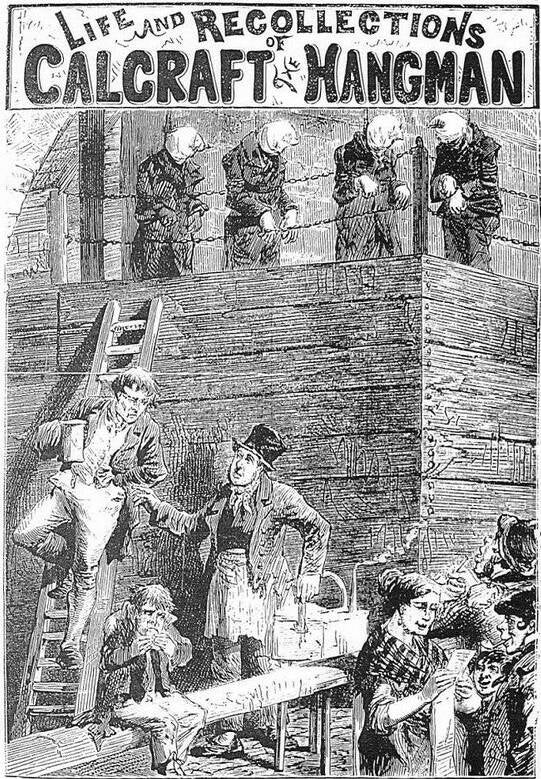

The young dissenter, Patrick McCaffery, swung on 11 January 1862 at the hands of Calcraft the hangman, in front of a crowd numbering 25-30,000.

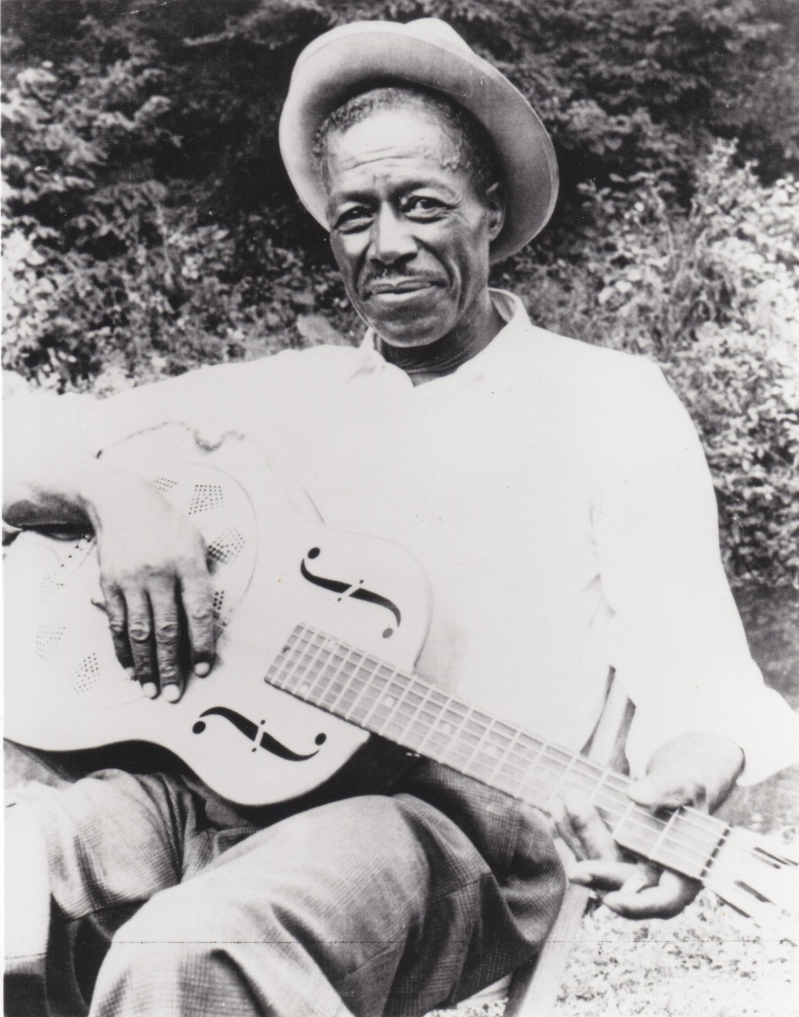

Jimmy MacBeath

3

Cornkister — generally a comic song from the 19th and 20th centuries, so named because the singer performed while sitting on a corn kist.

Before he became a bona fide star during the British folk revival, Jimmy MacBeath — pronounced the same as Shakespeare’s regicidal Scottish king — roamed far from the north-east fishing community of Portsoy, where he was born in 1894. Although farm labouring became a reliable source of employment for the young Jimmy, he also walked abroad through his service with the Gordon Highlanders in the first world war and a period lumbering in Nova Scotia, where he erroneously believed he’d find the streets paved with gold.

Farm labouring could be a brutal enough station at the best of times, but MacBeath particularly suffered at the hands of one employer who beat him with a cart chain for not controlling his horse. Unsurprisingly, MacBeath concluded that tramping around the highways and byways of his native Scotland would be a much less troublesome way of earning a crust, and on the road, he learned new songs from farmers, fishermen, and the Travelling class, as he called them. He slept in barns or, if he had good overcoat, he might rough it in the roadside or in a field. In one of his interviews with Alan Lomax he explained how there was nothing like waking up to a lark singing on a summer morning.

During one memorable episode, MacBeath recalled walking the 114 miles from Perth to Inverness without any food. A local police sergeant suspiciously noted his arrival and interrogated MacBeath until he realised there was no badness in him. The sergeant then had his wife feed MacBeath a hearty breakfast before he took to the road again after discovering MacBeath had nothing to eat.

MacBeath sang in markets and fairs, in pubs and on the road, often singing in the Romany “Cant” of the Scottish Travellers — one of the best known examples of this is Hey Barra Gadgie, which MacBeath learned in the north of Scotland.

MacBeath told Lomax he could understand only bit of the real Romany “Cant”, but that he could speak gibberish or slang “Cant”. And it was on the road that Jimmy MacBeath, in an act of dissent, sang McCafferty and made an unsuccessful getaway from the local constabulary.

Alan Lomax recorded MacBeath’s version of McCafferty in his flat in London in 1953 — the pair having first met in Turiff in 1951. In MacBeath’s almost broken version of the ballad, he inhabits the spirit of the dissenter Patrick McCaffery, owning the young soldier’s crime and his hatred for Captain Hanham in a powerful evocation of guilt: “I did the deed, I shed his blood.”

Alan Lomax

4

“Essentially, he believed that the main sources of music, dance, poetry and fantasy spring from the people who confront life’s joys and cruelties first-hand, in the raw, with little padding and few defences. He found out that the beautiful in music is honed over long eras and is nurtured by the local and the particular . . .”

— Anna Lomax Chairetakis, speaking about her father, Alan, at the 45th annual Recording Academy’s National Trustees Award ceremony.

Best known in his capacity as a folklorist for the Library of Congress, Alan Lomax was the first to record Huddie "Lead Belly" Ledbetter, whom he encountered in Angola Penitentiary, Louisiana in 1933, McKinley "Muddy Waters" Morganfield, and the great Son House.

Son House

By 1940, his recordings numbered in the thousands. However, it was through his political affiliations and sympathies that he achieved notoriety during the rampant scaremongering of post second world war America.

While the Great Depression saw the radicalisation of both the working classes and the intelligentsia, it was the struggles of the labour movement and the eventual formation of the Congress of Industrial Organizations that politicised Lomax. Although not openly a member of the Communist Party at this time, Lomax was quite active in their musical benefits. This, together with his association to suspected communists like Pete Seeger — whom he actively encouraged to use his talents as a weapon to agitate on behalf of the downtrodden — and leftist organizations such as the Steinbeck Committee to Aid Farm Workers and People’s Songs put him in Senator Joseph McCarthy’s gunsights and placed him on the dissenting side of American politics at the time.

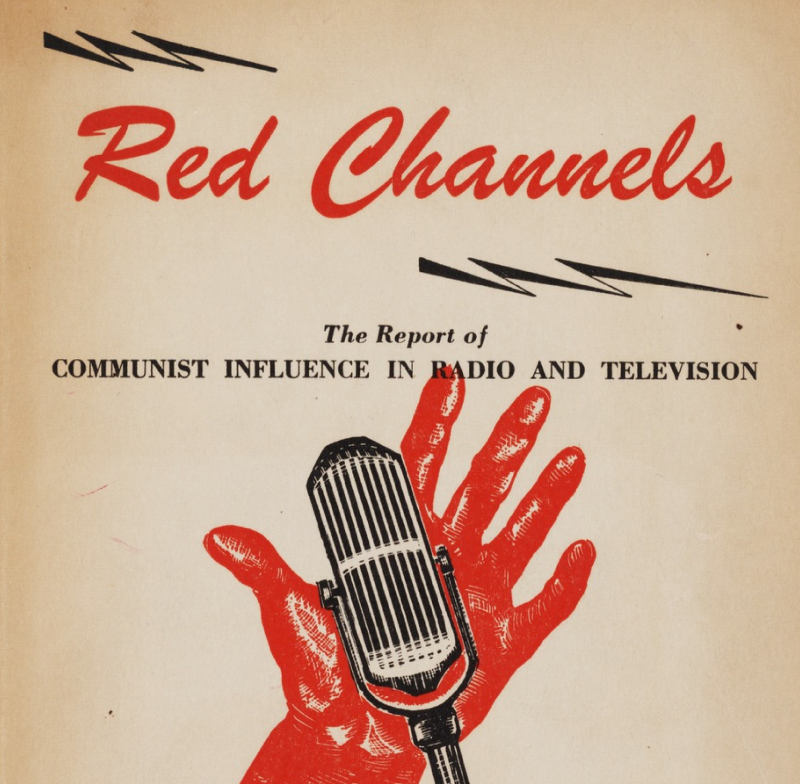

June 1950 saw the publication of Red Channels, a booklet listing 151 individuals from the broadcasting industry suspected of subversive activities. Three former FBI agents had established the vigilante organisation behind the booklet, American Business Consultants, to fight communism. Red Channels listed the organisations and activities each individual reportedly associated with, and the publication formed a blacklist within the industry to deny work to those named: including Alan Lomax.

As a victim of the “Red Scare”, Lomax departed the US in 1950, ostensibly to collect recordings for World Library of Folk and Primitive Music for Columbia Records, but the inability to work in his own country must have contributed to his decision. For the next eight years he worked in Europe rather than North America, and as a result he left an indelible mark on the recording of traditional and folk music in Britain and Ireland in particular, where he visited in 1951 to expand both the BBC and Radio Éireann’s catalogue of regional folk recordings and to record the Irish LP of his World Library of Folk and Primitive Music.

Recording Jimmy MacBeath’s version of McCafferty wasn’t Alan Lomax’s only encounter with the ballad. In his role as a compiler and editor of the Topic Records series, The Folk Songs of Britain, a version of the ballad, performed by Peter Reilly, appeared on Volume 8: A Soldier’s Life for Me, released in 1961 — which, incidentally, features Jimmy MacBeath performing The Forfar Soldier. Reilly, from Cullyhanna, County Armagh, gives the ballad a sorrowful air, presenting it as a dirge for the tragic Patrick. Against MacBeath’s version this must have presented a powerful and stark contrast to Lomax.

It stands to reason that County Armagh native Seán O’Boyle, himself a noted collector of music, contributed this recording to the compilation. O’Boyle came from the nationalist community in Armagh, but he would often travel to pubs in unionist areas to collect songs, revealing yet another dissenter in our midst. At a time when there was little, if any, cultural, political, and religious exchange between the segregated nationalist and unionist communities in the north of Ireland, this was very much at variance with his broader community.

Through his work, O’Boyle developed a close friendship and collaboration with the Scottish poet, songwriter, and collector, Hamish Henderson, who had visited Armagh in January 1956. In a letter to Henderson, O’Boyle’s fondness for the Scot is clear:

‘Seamus, a Caraid … Never think for one moment because I’ve not written before now that I haven’t been thinking constantly of yourself and the times we had around Hogmanay and the times that we’ll have … Haven’t you my own scallywag outlook on life, love, drink, and all the more important aspects of our terrestrial sojourn?’

Henderson had also accompanied Alan Lomax through the Scottish Lowlands recording songs in the summer of 1951. In Henderson, Lomax found the ideal collaborator in many ways, because not only was he intensely passionate about recording his people’s music, but he was also a communist.

Alan Lomax, Hamish Henderson, and Seán O’Boyle, song collectors and dissenters all, their orbits intersecting with Jimmy MacBeath and Patrick McCafferty.

“Those in power write the history, while those who suffer write the songs.”

— Frank Harte

5

Folk music is the sound of dissent. This tradition echoes back far beyond Patrick McCaffery, because the downtrodden have always used story and song to agitate against their oppressors. In folk music, we find opposition to the political and commercial actors who maintain the status quo on behalf of the few: That tradition continues today in the music of Lankum and Grace Petrie.

Much of Lankum’s music stands in solidarity with the oppressed. On their 2015 song, Cold Old Fire, they sing:

“We hear the sounds come streaming across the crackling air,

The broken words of swine who would tell us that we were

Born to live and lie and die in embers of a cold old fire nobody remembers,

They hand the ashes back to me down the button factory, we’re cattle at the stall.”

Here, they articulate the struggle of another broken Irish generation after the brutal infliction of austerity on ordinary people during the recession. They further explore this theme in the ballad, Déanta in Éireann, released in 2017, which documents the mass emigration of the previous decade:

“In their hundreds and thousands, in gangs and in droves,

Well they’re packing their bags as they take to the road . . .”

Grace Petrie also sings about the infliction of austerity on the British working classes, together with the demonisation of refugees by Brexiteers, in A Young Woman’s Tale, released on her 2018 record, Queer as Folk:

“We were sold prosperity

Off working people's backs

And while we got mass-austerity

The rich got let off tax

And now the NHS is on its knees

And the ones who get the blame

Are people washed up on the shore

With nothing to their name . . .”

Dissent against their respective governments pervades both songs. Ian Lynch of Lankum sings: “In the Dáil sit the pimps, we are the whores.” Be under no illusion what those pimps did to their whores:

“With their cheap talk they fooled us, we were sold, we were had,

They took us by the hand and they led us to bed,

Bent us right over, punched us in the head . . .”

A Young Woman’s Tale comes for Margaret Thatcher and the Tories and takes Tony Blair for good measure:

“. . . The miners lost the battle

But the good guys won the war

I stayed up with my folks

They drank champagne till 6 AM

The morning that we saw the Tories

Out of number 10

But short-lived was the victory

From that May morning air

When came the bloody war in

Through the door of Tony Blair.”

But from seeds of dissent do Lankum’s Déanta in Éireann and A Young Woman’s Tale conclude with persuasive rallying cries:

“For it’s not too late to fight back and these tyrants eject,

Take back what’s ours from these primates erect,

Our purpose, our lives, and our own self-respect,

Then we’d have something to be proud of in Éireann.”

—

“Now I know less than ever

What tomorrow's got in store

But I owe it to my children

To try for a little more

Than cruelty and division

Folks left in poverty to die

And if we've got a chance to change it

Then I'm damn well gonna try.”

Listening to these songs there can be no doubt that agitation is alive in our music. They are a necessary reminder for people to not only stand in solidarity with the most vulnerable in our societies, but to also stand against their oppressors, against the few who would keep them in destitution. But the last word on this must go to Florence Reece, the Kentuckian songwriter and agitator:

“My songs always goes to the underdog — to the worker. I'm one of them and I feel like I've got to be with them. There's no such thing as neutral. You have to be on one side or the other.”

Please support the artists featured in this story, Grace Petrie and Lankum.

Create Your Own Website With Webador