Hugh O’Neill, Earl of Tyrone.

“With the pretence of sending help to the King of Sweden, the English king has levied great numbers several times during these past years and scuttled the ships in which they were embarked. By various means he has achieved his purpose that none should return to Ireland alive. In all these ways he has procured to sap the strength of the Catholics so that, thus weakened, they may not resist the final blow which he intends to strike by depopulating the whole island of its ancient inhabitants who have possessed it for more than 3000 years when they came from Spain to live there. The expulsion is not merely a conjecture but a decree from the English Council of State which we were informed by secret means. There is nothing which the English king desires more for the glory of his crown than to assure himself of Ireland by depopulating it and establishing there those Englishmen who are in overabundance in his own kingdom.”

— Hugh O’Neill, Earl of Tyrone, writing to the Spanish Council of State in 1615.

King Karl IX of Sweden had problems in 1608. The war with Poland–Lithuania, a dispute over both his throne and the control of Livonia and Estonia, had started in 1600. Karl was under the cosh — he and his ally Tsar Vasili IV needed soldiers. And he got them from King James I of England.

King Karl IX of Sweden.

Between 1609 and 1613, approximately 3500 Irish swordsmen served in the Swedish army. This transportation of soldiers — sometimes voluntary, more often through coercion — was an integral part of Stuart foreign policy at the time and one of the many complex factors which paved the way for the Plantation of Ulster, a system of colonisation that involved the settling of Scottish and English people on Irish land, beginning in 1609.

“A project for the division and plantation of the escheated lands in six severall Counties of Ulster; Namelie Tirone, Colraine, Donnegall, Fermanagh, Ardmagh & Cavan: Concluded by his Ma[jes]ties Commissioners the 23rd of January 1608”. (Lambeth Palace Library).

Map of the Plantation of Ulster in 1622.

Many in Ireland believed that the transportation of these men was coercive and cruel. In fact, the policy of both Elizabeth I and James I had long been to encourage Irish soldiers to serve on the continent, thus easing overpopulation while simultaneously removing any potentially rebellious actors from the population. The opportunity to gain employment provided further motivation for the swordsmen to go abroad. Hunger also proved to be an effective tool. Swedish agents snared many a swordsman by promising him food rations upon enlistment. Going to the continent meant exile for the swordsmen concerned — the English authorities had no intention of allowing them to return home.

Hugh O’Neill’s letter to the Spanish Council of State reveals something of English plans concerning an Ulster free of Irish population lest they contaminate the civilised colonists. The Nine Years’ War — waged by O’Neill and Hugh Roe O’Donnell against English rule in Ireland between 1593 and 1603 — and the subsequent Flight of the Earls in 1607 ended the old Gaelic order in Ireland. O’Neill had trained his soldiers in modern military tactics and had left behind many effective infantrymen with a well-deserved reputation for toughness. Their very existence was both a military challenge and the antithesis of what the English hoped to create through the plantations — namely, the establishment of an English society in Ireland.

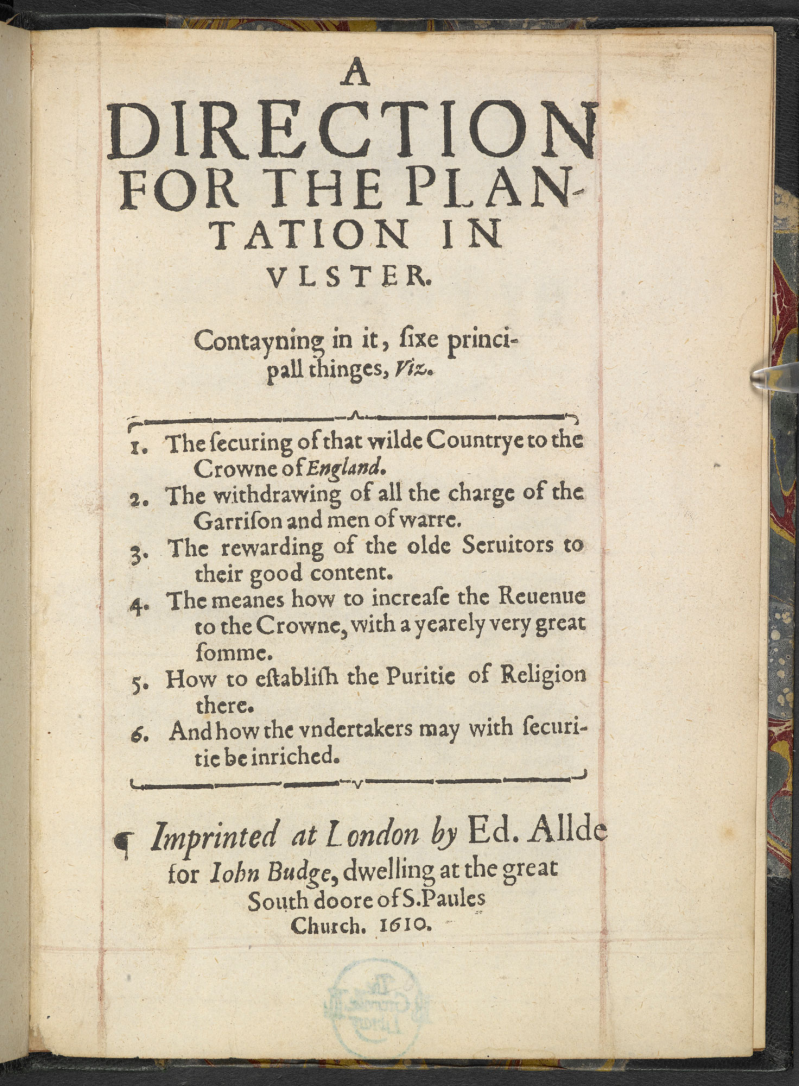

The removal of these ‘idle swordsmen’ — at the time there were 4000 in Ulster alone — was made all the more urgent by persistent rumours of Hugh O’Neill’s return to Ireland, and his intention to inspire an uprising by rallying the swordsmen behind his banner. Notwithstanding this threat of further rebellion, the swordsmen presence had already proved to be a deterrent to potential settlers, although English propaganda didn’t help much in this regard by depicting them as barbarous. A pamphlet published at the time, A Direction for the Plantation in Ulster, argued that the planters should hunt the swordsmen for sport.

But then an unexpected solution dropped into English hands. In 1608, King Karl IX sent an embassy to James I, asking the English king if he could recruit soldiers in Ireland to fight in his war against Poland–Lithuania. Having considered the matter, James allowed Swedish agents — some of whom were Scottish — acting for Karl IX to recruit in Ireland from 1609. Officials not only facilitated these Swedish agents, but also partly paid for the swordsmen’s transportation to Sweden as well as fitting them out in new clothes and shoes. The financially strapped English Exchequer forked out more than £6900 in this regard.

The English crown also rewarded several of the Scottish agents who had recruited and transported Irish soldiers to Sweden with large tracts of land — as much as 1000 acres — as part of the Plantation of Ulster:

“This grant is made in consideration of Capt. Sanford’s absence, during the distribution of the escheated lands in Ulster, in consequence of which no portion was assigned to him, he being then engaged in conducting the loose kerne and swordsmen of that province to the service of the King of Sweden, disburthening the country, by that means, of many turbulent and disaffected persons, who would otherwise have troubled the peace.

— The Patent Rolls of King James I, 14 March 1613.

Sir Arthur Chichester, Lord Deputy of Ireland.

As dark rumours circulated among the population about the transportation scheme, recruiting became difficult. Jesuits argued that it was a sin to serve the Lutheran Swedish king. Undeterred, Sir Arthur Chichester, Lord Deputy of Ireland, set about removing any potential opponents of the plantation, later claiming that he transported “6,000 bad and disloyal” Irishmen to Sweden. By the summer of 1609, he had started to zealously enforce a policy of coercion, press-ganging swordsmen into exile, and cleansing Ulster of as many dissenting actors as possible. To this end, he pardoned more than 1000 men who had taken up arms in O’Doherty’s Rebellion and others who had fought under O’Neill. Enforced enlistment and banishment was the price of their freedom, with Chichester dangling the threat of execution over their heads should they return. In justifying this course of action, Chichester called them “cruel, wild malefactors and thievs.”

Chichester also banished several rebel Irish lords. Among them was Oghy O’Hanlon, a man previously marked for execution by Chichester. That a policy of clemency prevailed in this instance shows how much the rumours surrounding O’Neill’s return had frightened Chichester and the English authorities. Some of these swordsmen managed to abscond en route to Sweden, with O’Hanlon orchestrating an escape of around 500 men. They joined the Army of Flanders in the Spanish Netherlands, where O’Hanlon became a captain in the Regiment of Tyrone.

In September 1610, Chichester exiled another 600 men to Sweden. More troops travelled in 1611, and by this point there were at least 2000 Irishmen fighting for the King of Sweden. Although Karl IX admired their skills as soldiers, he had misgivings as to whether they would remain loyal fighting against King Sigismund III, Poland’s Catholic monarch. Still, he pressed James I to recruit more troops in 1612 and 1613.

Of the roughly 5000 swordsmen engaged by the Swedes, at least half of them left Ireland against their will through various forms of coercion and banishment. Of that 5000, around 3500 made it to Sweden. The remaining 1500 swordsmen forged new lives abroad, with most of them heading to the Spanish Netherlands to enlist in the Army of Flanders. However, some of them risked execution by returning home. 1000 swordsmen died in battle or from illness and starvation while soldiering in Sweden. Another 1200 abandoned Karl IX for the Poles, proving the king’s instincts were correct. Some of those men stayed in Polish service, while others eventually left to join their countrymen in the Army of Flanders.

The Battle of Klushino.

The swordsmen who landed in Sweden lived in poor conditions. Cruel officers regularly stole their wages. Priests going incognito sowed sedition among the men, encouraging them to fight for Poland. In June 1610, at the Battle of Klushino, many Irish swordsmen deserted the large Swedish force to fight with the much smaller Polish army. This mass desertion helped to secure victory, one of the most memorable in Polish history.

The story of the swordsmen ‘recruited’ by Sweden in the early 17th century is but a small part of the history of both the Irish military diaspora and the Plantation of Ulster. However, the expulsion of the swordsmen did significantly contribute to the success of the plantation by removing those actors whom the English viewed as rebellious. History has forgotten them, overshadowed by their more famous cousins who departed Ireland in 1607.

Create Your Own Website With Webador