At the bottom of narrow road bordered by earth ditches in north County Kerry, Ireland, the Kilmore Burial Grounds sit atop a cliff face overlooking the Atlantic Ocean. Surrounded only by a nondescript wall, the graves remain unmarked save for a single white cross.

Standing at the south end, one can see the Shannon Estuary and County Clare straight ahead, while Kilmore Strand and the mouth of the Cashen River lie to the east. Turning to the west, the vastness of the Atlantic Ocean stretches out — next stop, America. The Atlantic winds blow strong here.

View from Kilmore Burial Grounds, Co. Kerry, looking west to the Atlantic Ocean.

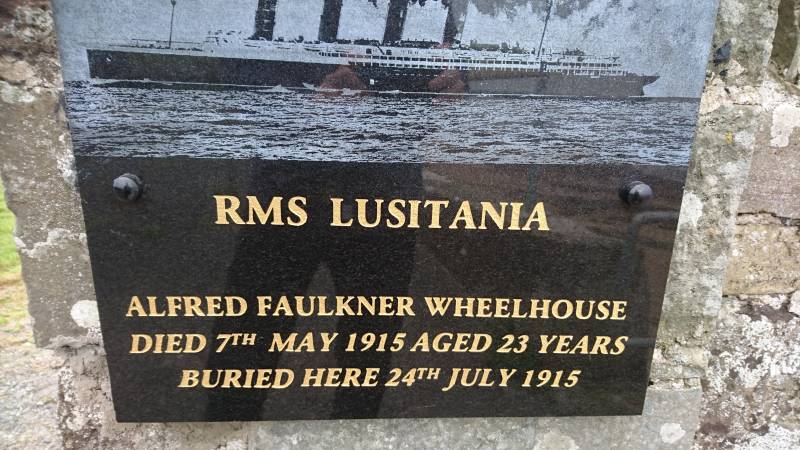

On the wall, next to the gate, is a plaque dedicated to Alfred Faulkner Wheelhouse, who perished aboard the RMS Lusitania on 7 May 1915, before his burial in Kilmore on 24 July, aged just 23. Anyone familiar with this windswept and rugged part of the world might find the name Wheelhouse a peculiarity around the townlands of Clahane and Kilmore. How Alfred Faulkner Wheelhouse came to rest in a small burial ground in rural Kerry is a harrowing chapter in a much greater tragic story. At the very heart of it all is a grieving mother who found solace in making a pilgrimage during the first world war to say goodbye to a son lost at sea.

Plaque dedicated to Alfred Faulkner Wheelhouse, Kilmore, Co. Kerry, Ireland.

***

Born in Hulme, Lancashire, in England, in late 1891, Alfred Faulkner Wheelhouse was the only son of Frederick William Faulkner and Matilda Wheelhouse to survive into adulthood. Although bereaved of his four brothers, Alfred did have an older sister by three years, Sarah, who worked in the Post Office in Bridlington. By 1915 his father had died and records show that the family now called Bootle, in Liverpool, home.

Alfred was a career engineer. On 12 April 1915, the famous Cunard Steamship Company hired him as a Junior Seventh Engineer on board the doomed Lusitania with a monthly salary of £10. Reporting for duty at eight in the morning, Alfred set sail on 17 April, never to see Bootle again.

Launched on 7 June 1906, the Lusitania was the largest passenger ship in the world at 240 metres in length until the Mauretania, her sister-ship, surpassed her the following year. While nominally a luxury liner, the Lusitania had a reputation for speed, winning the Blue Riband for the fastest crossing of the Atlantic in October 1907, averaging 24 knots. The Mauretania would later claim the Blue Riband, although the two ships would regularly compete for the honour.

In May 1915, the Lusitania made her return leg voyage from New York to Liverpool, carrying 1,959 passengers. The British Admiralty had warned the Lusitania to avoid the area off the south coast of Ireland due to German submarine activity and the sinking of merchant ships. Furthermore, they recommended the Lusitania change her course at irregular intervals to confuse any U-Boats attempting to track her course for torpedoing.

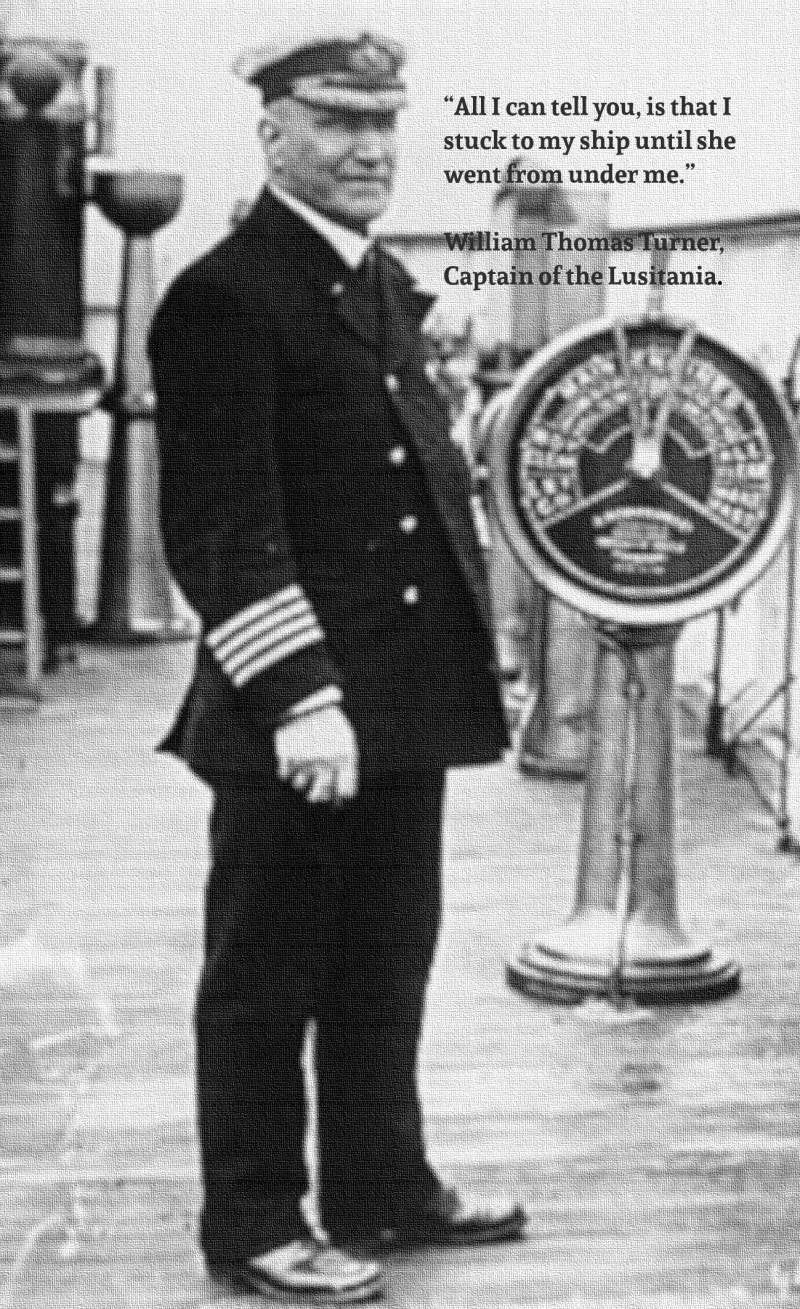

William Thomas Turner, the Lusitania’s captain, ignored these warnings, and on 7 May, within sight of the Old Head of Kinsale in Ireland, a torpedo fired by U-20, under the command of Kapitänleutant Walther Schwieger, struck the Lusitania amidships on the starboard side, exploding afterwards. 4,200 cases of small arms ammunition carried on board were potentially the cause of a second, heavier explosion. 20 minutes later the Lusitania had sunk, drowning 1,198 people, Alfred among them.

It is impossible to say how Alfred Faulkner Wheelhouse reacted when the German torpedo struck. However, testimony from another engineer, Andrew Cockburn, given at the investigation into the sinking presided over by Lord Mersey at Central Hall in Westminster, gives a sense of what those working aboard the Lusitania experienced as she foundered.

Engineer Cockburn testified that when the torpedo hit, he was outside his cabin on ‘C’ Deck, and immediately descended into the engine room to find the watertight doors already closed. He put on his lifebelt and talked to the Chief Engineer, Archibald Bryce. With the engine room now in darkness and all the steam gone, Cockburn could hear water rushing inside but could not tell exactly from where. At this point he understood that there was nothing further he could do to save the Lusitania, so he went up on deck to find her severely listing to starboard.

Cockburn then climbed over the deck rail and jumped into the sea just as the Lusitania sank. After struggling back to the surface against the pull of the sinking ship, he kept himself afloat by holding on to a valise and later the top of an upturned boat. The Royal Naval Trawler Indian Empire eventually rescued him from the water. Had Andrew Cockburn lingered in the engine room any longer, he most certainly would have gone down on the Lusitania with Alfred.

***

“I naturally was looking for a Church but there is no Church anywhere near, it is just a piece of ground walled off. At the time I felt disappointed. Anyone always living in England would do, but the people think it quite nice. But I have never seen a place like it before for a Church yard.”

— Matilda Faulkner, in a letter to a Cunard Steamship Company official in Liverpool, 9 August 1915.

After eleven weeks in the water, what remained of Alfred Faulkner Wheelhouse washed ashore on Kilmore Strand on 24 July. The Atlantic had brutally severed his head and arms, part of his body, one of his legs, and his remaining foot. Before his burial that evening in the Kilmore Burial Grounds, the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) removed any personal items still on his person, including a silver matchbox with the inscription: A. Wheelhouse. The Cunard Steamship Company received a telegram from the local RIC barracks in Ballyduff reading:

“Body of a man washed ashore at Kilmore . . . No clothes except trousers, black serge, in pockets, gold watch No. 71649 words English make, this case guaranteed to wear 10 years, Lancashire Watch Company Ltd., Prescot, England on dial, double breast gold chain curb pattern around seal suspended in centre, silver match box attached to chain with name A. WHEELHOUSE engraved on it. Sixpence in silver and one cent.”

Alfred’s mother, Matilda, on receiving the news of his death, told the Cunard Steamship Company of her wish to visit Kilmore. An official from Cunard — whose name we do not know — in Liverpool, contacted RIC Sergeant William Best in Ballyduff by post and telegram in order to facilitate Matilda’s visit to Ireland. Both men agreed, considering the condition of Alfred’s body, not to reveal the state of her son’s remains. However, they did tell Matilda that several local people attended his funeral and that several of the women keened over his coffin, as was tradition in Ireland at the time, in the hope this might give her some respite from her grief.

Matilda travelled to Kilmore in early August 1915, at Cunard’s expense, by sea and rail. Sergeant Best met Matilda at the train station and brought her to the burial grounds. After Matilda had seen Alfred’s grave, Sergeant Best promised her that he would erect wooden railings around his grave to mark its location. The pilgrimage to her son’s grave seems to have had a profound effect on Matilda, and in some small way provided her with a sense of closure. In a letter to the Cunard official, she said:

“I know well that it is only the body there but I am very glad I have been and I have thought it well over. There are many that do not know where their dear ones are laid, but I know I can think of the place where my dear Boy’s body is laid. I am sorry I cannot ever repay you for your kindness to me, but I sincerely thank you with all my heart.”

And of Sergeant Best, she said: “Sergeant Best was very kind, if it had not been for him I never could have found the grave — as it is a wild place.”

Reading Matilda’s description of the Kilmore Burial Grounds, it is striking how little it has changed since her visit. The wildness of the place, the bare graveyard, it’s as though she could be standing there again today, over a century later.

The Kilmore Burial Grounds, looking north. Matilda Faulkner described it as ‘a wild place’. If Sergeant Best ever erected the wooden railings, they do not exist today.

Despite efforts by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission to mark Alfred’s grave in Kilmore, they decided that maintaining a memorial to him at the site would be too difficult considering the absence of any headstones and the local authorities had at that point abandoned the grounds. However, the commission included Alfred’s name on the Mercantile Marine Memorial at Tower Hill in London.

But what about the plaque in Kilmore? Remarkably, 104 years after his death, the community around Kilmore and nearby Ballyduff still know of and remember Alfred Faulkner Wheelhouse. In June 2016, the pupils and teachers at Sliabh a'Mhadra National School in Ballyduff, together with members of the local community, dedicated a plaque to the memory of a drowned engineer from Lancashire.

Thinking now about a man who died over a century ago, one can’t help but ponder whether the ancestors of those who erected the plaque might have attended Alfred’s funeral. In a place where a family, and indeed memory, can stretch back many generations, this seems entirely plausible.

Fishermen from the Cashen, early 1900s. Could some of these men have attended Alfred’s funeral?

***

In 1915, the people of Kilmore believed they had committed Alfred’s remains to the earth, where he would rest in peace, undisturbed. But there is another twist to this story yet. Situated precariously atop a cliff, the burial grounds have experienced coastal erosion and as such there is a suspicion locally that a heavy storm washed Alfred’s remains away from the north end of the grounds some years ago. So it goes that the Atlantic came back for the rest of him, she just couldn’t let the man be.

Create Your Own Website With Webador